Of the debris removed from estuaries is from damaged and/or lost docks, piers, boat houses, and similar structures

Pounds of debris have been removed from public trust waters so far

Legislative Changes for Docks and Piers in North Carolina

In 2023, Federation staff worked diligently alongside legislators to advocate for two legislative actions that would help to reduce marine debris. One focus of her work was to prohibit unencapsulated polystyrene, a material commonly used in the construction of floating docks. The state General Assembly enacted a pioneering ban on this material that’s unparalleled by any other state in the nation. This ban now necessitates the encapsulation of polystyrene within coastal counties. Unencapsulated polystyrene is inherently fragile, rendering it susceptible to damage even during minor storm events. When these materials break apart, they release numerous tiny foam beads into our coastal ecosystems, where their removal becomes a nearly insurmountable challenge. With the state’s move toward a statewide law, our entire coast is now protected from this entirely avoidable marine debris. This ban prohibits the sale of unencapsulated polystyrene from being used in the construction of floating docks.

The second major achievement was the decision by the state General Assembly to cover residential docks built along our coast under the state’s building code. This will help make sure that docks are built in a way that will make them more resilient to damage during extreme storms. To read more about the changes the state has made check out House Bill 600, the information regarding docks and piers begins on page 32.

The Aftermath of Hurricane Florence

Hurricane Florence caused extensive and significant damage to many residential docks & piers along our coastal estuaries. Chemically treated lumber, floats, polystyrene, and other debris from these docks were scattered over hundreds of miles of our shorelines, yards, waterways, and marshes. This debris damaged downstream homes and landscaping. It was found in public trust waters, public parks, vast areas of wetlands, and on numerous sound side islands. Some of this debris is classified as hazardous waste and it also creates hazards to navigation.

Recognizing the extent and impacts of the debris on the coastal environment and economy of fishing and tourism, the North Carolina General Assembly awarded funding in 2019 through the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality to the Federation to remove debris from public trust waters that fall outside the scope of traditional cleanup programs. The project focused on consumer and heavy wooden debris from damaged docks and piers that had washed up after the storm.

With additional funding from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service Emergency Watershed Protection Program, and the N.C. Division of Coastal Management the Federation removed a total of 888 tons of debris just in the first six months.

To date, over 3 million pounds of debris have been removed from public trust waters.

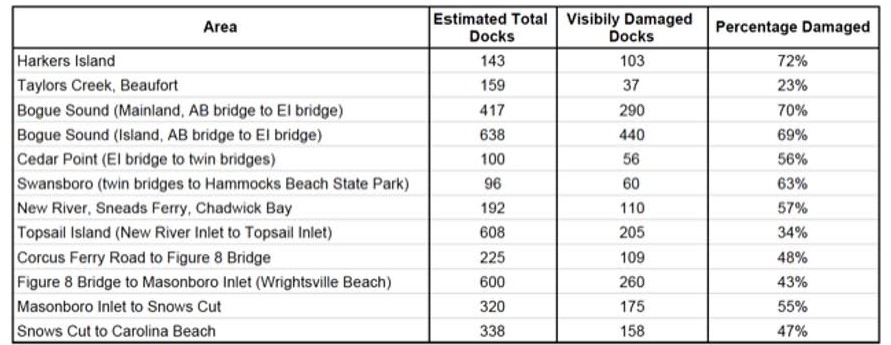

Using NOAA’s aerial imagery acquired post-Florence, Federation staff completed an assessment of storm-damaged piers and structures along the Central and Southeast coasts. This survey revealed significant portions of the coast where the remnants of docks and piers were littering public trust waters. Through field surveys, crews reported over 85% of the debris removed from North Carolina’s estuaries between 2019-2022 is the result of damaged and/or lost docks, piers, boat houses, and similar structures.

Many examples of damaged and/or lost structures are the direct result of substandard marine construction techniques, including lack of expertise/experience, poor construction, substandard materials, and cutting corners on both construction methods and materials.

As part of the NOAA grant, a robust stakeholder group comprised of engineers, regulators, and scientists developed recommendations that contributed to the report: Recommendations for Improved Marine Construction to reduce damage, losses, and marine debris resulting from storms in North Carolina.

These recommended standards for the design and construction of residential docks and piers were drawn not only from the stakeholders’ expertise but also from best management practices implemented across the country.

As seen in the report, recommendations for marine construction materials, techniques, and practices vary, depending on location, wave energy, property owner preference, designated use, and cost. As such, further work is needed before standardized recommendations can be made; however, one exception is the use of polystyrene foam.

Expanded polystyrene foam is a common material to use as dock flotation because it is light and inexpensive. However, the environmental and social costs of this non-biodegradable material far outweigh its trivial benefits. When exposed to the elements, unencapsulated polystyrene will become brittle and crack, potentially crumbling into thousands of foam beads/fragments that destroy the aesthetic and health of shorelines and threaten aquatic ecosystems.

Furthermore, polystyrene contains chemicals such as benzene, styrene, and ethylene. In small quantities, these chemicals can leach into the water, and in larger quantities, can pose significant health risks. Also, other toxins can easily bind with polystyrene’s molecular structure. As a result, dock foam often poisons marine animals, as polystyrene concentrates and magnifies these toxins. This toxicity moves up the food chain, affecting entire ecosystems and eventually humans.

To prevent foam deterioration and pollution, a process known as encapsulation secures the floating foam material, protecting it from the elements. A thick, plastic shell is thermally formed around the foam bricks, making them more resistant to impacts, impermeable to water, and a more rugged component for the floating dock system. Economically, paying for encapsulated dock foam is initially more expensive than purchasing unencapsulated foam, but the investment quickly pays off. Encapsulated docks last significantly longer, require far less maintenance and eliminate the potential risks unencapsulated docks pose. They prevent toxin magnification, save the lives of marine animals, and ensure a healthy and aesthetic ecosystem.

As a result, four towns in North Carolina – Topsail Beach, Surf City, North Topsail Beach, and Wrightsville Beach – have adopted ordinances requiring the encapsulation of polystyrene foam.

To learn more about this effort, and how your Town can become the next to adopt an ordinance, check out pages 18-33 of our report on microplastics and floating docks.

If you have any questions, please contact Kerri Allen, Coastal Management Program Director, at kerria@nccoast.org or 910-509-2838 ext 203

Resources

- North Carolina State Building Code 2009

- Tie It Down! A Coastal Property Owner’s Guide to Preventing Marine Debris

- Report on Microplastics and Floating Docks in Southeastern NC

- Recommendations for Improved Marine Construction to reduce damage, losses, and marine debris resulting from storms in North Carolina

Tackle Trash

You can help clean up our coast—from hurricane debris to microplastics.